Platforming like it’s 1986

In the year 1985 there was this now legendary game Super Mario Bros on

the SNES. Our family never owned a SNES, but my brother did have a ZX Spectrum.

The Spectrum was a relatively cheap 8-bit micro, and despite being a very

underpowered computer with blocky graphics, it does have some games that are

pure gems. One of those games is the 1986 title Cobra, an action platformer

that is maybe best described as “Mario with guns”. The game is a bit of a

cult classic, being revered as a technical achievement, but also hated

for being too damn difficult. Like many old games, it’s hard as nails;

it requires timing the attacks just right. I’ve been wanting to do a platformer

game for a long time now, so I set out to build a clone of Cobra.

In the year 1985 there was this now legendary game Super Mario Bros on

the SNES. Our family never owned a SNES, but my brother did have a ZX Spectrum.

The Spectrum was a relatively cheap 8-bit micro, and despite being a very

underpowered computer with blocky graphics, it does have some games that are

pure gems. One of those games is the 1986 title Cobra, an action platformer

that is maybe best described as “Mario with guns”. The game is a bit of a

cult classic, being revered as a technical achievement, but also hated

for being too damn difficult. Like many old games, it’s hard as nails;

it requires timing the attacks just right. I’ve been wanting to do a platformer

game for a long time now, so I set out to build a clone of Cobra.

Mapping the map

First off, 2D platformers need a tile map renderer. While such a tile renderer is nothing too complicated, bootstrapping a world map is a bunch of work. You are literally creating a game world from nothing.

The best thing you can do is to start building a basic map editor. I know, you don’t want to make a map editor; you want to make a game—but believe me, there are few things more rewarding than seeing a game come to life, as you’re editing the map while playing it (!)

A tile map is nothing but a 2D array of bytes that represents the game world. Each byte is a tile. Some tiles are platforms, while others may just be background art. Rendering the tile map is as easy as looping over the 2D array and rendering the tiles that are in view.

The ZX Spectrum has a low resolution screen of only 256x192 pixels, a 4:3 ratio. The actual gameplay area of the Cobra game is only 256x144, which is a more pleasant 16:9 ratio, that we can easily scale up to common modern resolutions without letterboxing. Still, this resolution is offensively low, giving huge chunky pixels. This res is much lower than most retro games, and it seriously made me consider doing an upscale of the graphics.

Platforms

Tiles are blocks of 16x16 pixels. A platform is a horizontal row of blocks in the tile map that the player can stand on. To know whether the player is on a platform, you have to check the tile right below the player position.

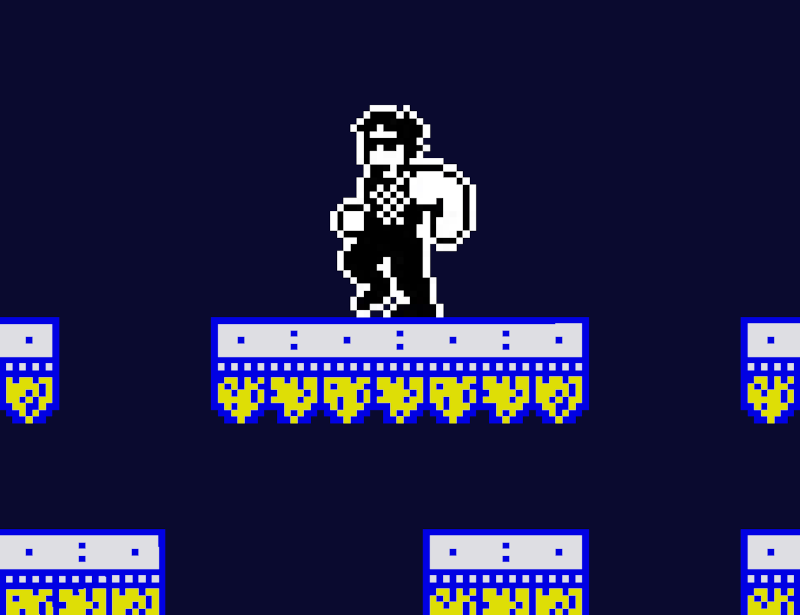

Screenshot: Our hero standing on a platform.

Code for standing on a platform:

bool player_on_platform(void) {

int tile_x = player.x % TILE_W;

int tile_y = player.y % TILE_H - 1;

assert(tile_y >= 0);

byte tile = tile_map[tile_y * TILEMAP_W + tile_x];

return is_platform_tile(tile);

}

Pretty simple, right?

When the player walks off a platform, the hero will fall. You don’t have to apply gravity all the time, platformers are not physics simulations (well … most aren’t). More on gravity later, but I found things became a lot easier when I introduced move states:

typedef enum {

MS_STANDSTILL = 0,

MS_WALKING,

MS_JUMPING,

MS_FALLING,

...

} MoveState;

In particular, notice that jumping and falling are two different states. Jumping is going up, and falling is coming down again. The player may jump up ‘through’ a platform, but when falling, the player will not zip through, landing on the platform.

It is important to realize the little details of exactly how movement works, and this must be written in code—otherwise the game won’t work.

Jumpman

Jumps have a parabolic trajectory. The player character moves in the x-direction with constant speed, but the y-direction accelerates to form a parabola.

dx = velocity.x * dt;

dy = velocity.y * dt + 0.5 * g * dt * dt;

// accelerate

velocity.y += g * dt;

Remember from physics class that gravity g is 9.8 m/s2, but that doesn’t work because our game world isn’t defined in meters—it’s in pixels. To make the parabolic jump seem believable onscreen, we must use a different value for gravity. We can calculate a good value for gravity by rewriting the formula for a parabola as such:

At its highest point, the velocity will be zero. This means that the term velocity.y × dt can be left out. At its highest point we have:

h = ½gt2 ⇒ g = - (2 × h) / t2

I want the jump to be 1.5 tiles high (24 pixels), and I want it to last 0.8 seconds. The highest point is reached after 0.4 seconds. Plugging this into the formula gives a pseudo-gravity of about minus 300 which may seem like a large value, but do mind that dt will be one-sixtieth of a second (the game runs at 60 Hz) and the movement formula multiplies by dt squared. So, per game tick the actual delta y movement is quite small.

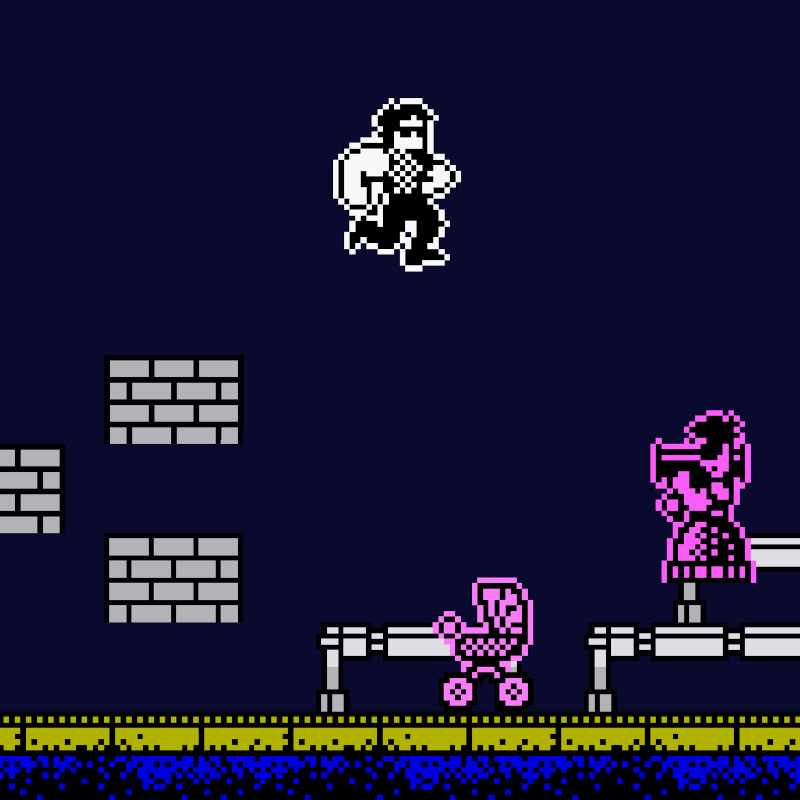

Screenshot: Our hero jumping off a high platform.

While I like the tightness of the perfectly parabolic jump, note that many platforming games tweak jumping in order to make it feel right. Super Mario for example falls faster than he jumps; for the second half of the jump the gravity parameter is different, higher. This results in a floaty jump that is defining for how the game plays.

Not quite like 1986

Up till now we’ve been rendering the tile map by looping over the map and drawing the individual tiles one-by-one. With modern hardware we can do a lot better than that; our game world is small enough to fit into a single large texture, meaning that we can render the entire background in one single draw call.

In order to pull it off, we have to create a target texture, and then pre-render the tile map to that texture when loading the level. We’ll use that texture for rendering the background during gameplay.

SDL_Texture* target;

target = SDL_CreateTexture(sdl_renderer,

SDL_PIXELFORMAT_RGBA32,

SDL_TEXTUREACCESS_TARGET,

w, h);

SDL_SetRenderTarget(sdl_renderer, target);

clearscreen();

int xp, yp = 0;

for (int j = 0; j < TILEMAP_H; j++) {

int row = j * TILEMAP_W;

xp = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < TILEMAP_W; i++) {

byte tile = tile_map[row + i];

render_tile(tile, xp, yp);

xp += TILE_W;

}

yp += TILE_H;

}

Going through the trouble of doing so is worth it especially because of heat issues; an overheated laptop cpu (and gpu) will throttle down, resulting in jarringly low performance, even while running a seemingly simple game. The venerable ZX Spectrum never had such issues.

Mathematically speaking

We’ve been using a tile map for platforming, and this is indeed the oldskool way of doing things. A modern take however is a more mathematical approach.

In its most mathematical form, a platform is nothing but a line segment between two points A and B. Whenever the player is between A and B, the hero may be on the platform. If player is above the line and falling through, then the hero should land on the platform.

That’s all there is to it, really; taking this approach makes the entire thing seem trivial.

Release mode

My version of this game is in good shape, but when people ask ‘is it finished?’, I have to tell them ‘no’. Even for a small game like this, coding the entire thing from A to Z and outputting a finished, polished product is a tremendous amount of work.

“You have no idea how much work it is to make a game, unless you’re making games”.

—Jonathan Blow, game developer

I have only gained more mad respect for the genius programmer behind the original Cobra game, Jonathan Smith. He was in his early twenties and coded the game in a couple of months, in 100% ZX81 assembly code.